When I reflect on the work that I see, I think about the ways in which I’m affected on a few levels.

As an artist, I think about whatever I see in terms of its part within a dialogue in which I’d like to be engaged, an ongoing negotiation of what performance is and can be. Was I inspired by the work? Was there innovation of form? Was the execution solid? What were the original ideas at play? What can I steal? Work that I love inspires me, but I actually like seeing a piece that I hate—it energizes me to think about what I want my own work to do and be.

Sometimes, a piece will make me forget to consider these terms—I get lost in its world, transported to another space. It’s nice when that happens. Of course, afterwards I’ll reflect on it, dissect it, consider what it was and why it worked.

I can break apart a performance into what might be considered its component pieces—the movement of bodies, the language, the visual elements, the sound, the acting, the trajectory of event, the relationship to the audience, the relationship to the space, the use of possibilities, what I might perceive as the message or mission of the piece. There’s also the element of how the piece held my focus, and if it had grabbed me, what it did with that focus once it had it. I’m sometimes surprised by what holds my attention onstage—some performers have a presence that I find difficult to look away from. Some activities onstage are endlessly absorbing to me to watch. It doesn’t always make sense what does or doesn’t interest me onstage, but I try to clock when I find myself unable to turn away from something, when it has me on the edge of my seat.

Suspension, in a word. When a piece can achieve suspension—of disbelief, I guess, but more a suspension of ‘knowing’. If a piece can keep me aloft in a state of not-knowing, but of wanting-to-know, I find that endlessly absorbing and pleasurable. Without that buoyancy, why bother? Why bother making it, and why bother sitting through it?

Suspension can be intellectual, emotional, imaginative, physical. In some way, it’s about a belief in the possible.

—————————————————————————–

On Monday night, I attended what could possibly be thought of as the last piece of 1419’s first and only Theatre Season. Jeff Shockley’s Epilogue Project has been in development for about four years now. This past weekend (April 1-4) he presented work at a series of locations, including 1419, where I caught a showing. I didn’t know what to expect going in. Jeff’s a good friend of mine; we’ve hung out since sophomore year when he roomed with one of my classmates. I was impressed by his epic pipes (one in the shape of a dragon!) and we bonded. Jeff was a major influence in getting me involved with 1419, and he’s been one of the big brains in my life over the last year or so.

Over the last few years, the Epilogue Project has had various incarnations as a blog, a draft of a play, a series of workshops, and most recently, a facebook group, a camping retreat, and this past weekend, a series of presentation/performances by Jeff. (More on the history of Epilogue later).

I was one of around a dozen people to decamp to Door County, Wisconsin in mid-March for the Epilogue Retreat. It was a really fantastic time–a utopia project that had all the right ingredients (including an expiration date) to succeed in creating a beautiful heterotopia for its participants for the span of a few days and nights spent in cold-ass Wisconsin. [The term heterotopia is gonna get thrown around a bit here, just a heads up. Michel Foucault originated the term in his essay Of Other Spaces. In a nutshell, a heterotopia is a space where the rules of normal life don’t apply, a space that is self-contained and operates under its own logic. Examples of heterotopias include Disneyland, cruise ships, and The Vatican.]

Other than attending the Epilogue Retreat, I haven’t had much involvement with the project. I was so taken with Jeff’s presentation at 1419 that I asked him to record a conversation/interview with me, which is quoted below and organized sort-of thematically.

First off, though, a description of what actually occurred on Monday night: I asked Jeff what the ‘score’ for the night might be, if, say, someone else wanted to perform the piece. Here’s what I asked, then what he said, and then what I said, and then what he said:

Ben: It struck me that because it was so task-based, if there was a performance score for last night–what would the score be? If you had to hand someone a script to perform Epilogue as it was last night, what would it be?

Jeff: Oh, um. The truth is that I think that it can’t ever be done again. Because I made it in that moment and it happened with those people, then it was done. I could could give you the score–

B: Well, if I wanted to put it in a book about something, or for instance write something about it–

J: What happened–

B: What was the score for the night?

J: Well, you have to establish a lobby space where there’s a long table, and on one side of it there’s a bunch of chairs that look exactly the same that are right next to each other and are really kind of close to the table so that you’re sitting at the table when you’re sitting on the chairs. You have to direct people to sit in the chairs as sort of a lobby space, in the uniform chairs. And then on the other side of the room, across from the table, there’s a bunch of different kinds of chairs, um, whatever chairs that you have that don’t match the other chair. And you set them all up and you don’t let anybody sit in those yet. And you take one person at a time, if this is at 1419, where it should be, and you walk with them all the way up to the roof, and along the way there’s this little monologue thing, which is. If I don’t know them, I say hi, I’m Jeff, what’s your name, and meet them. I say, have you ever been to this building before? and ok, if they haven’t. And I say, OK, I’m gonna take you all the way up to the roof now, and there might be some other people up there and there’s some blankets up there and I’m gonna have you lay down if you could, or if there’s no room to lay down, you could just stand up and look straight up. And what I actually say right before that is, the performance will begin when you come back downstairs and sit down. I’m gonna have you do something, and then you’re gonna come back downstairs and sit down and the performance will begin. So you’re gonna go up to the roof. You’re gonna lay down or stand and look up, and you’re gonna focus on a star. There’s some stars out right now. You’re gonna look at it, and you’re gonna focus on it, and what I want you to do is to forget that it’s a star, to not recognize it anymore as a star. It might take a while, it might be hard, so if you wanna take a break, you can look down or chill out for a minute and that’s fine. Just keep focusing on it, the star. And when you forget that it’s a star, when you no longer recognize it as a star, that’s when you come back downstairs and sit in one of the other chairs. That’s what you tell them. And so then they do that–you could also lay out some blankets beforehand, that would be a nice thing to do for people. And then you keep doing that to every person that’s on the unified chair side of the table. And you should wait for everyone to come back.

The score for the last part was, perform. For the people that have come.

B: That’s it?

J: Yeah. And what I ended up doing was to arrange the chairs, sit in one, apologize for not being able to perform, and then put the chair back, and then sit down and say it’s over.

B: What do you mean by ‘perform’?

J: In the way that I was performing on Friday and Saturday it was existing. Performing as human in constant state of inspiration or human in completely… human constantly having new thoughts or human not having rational thoughts. It’s kind of like performing being in the heterotopia.

B: Why not just be in the heterotopia? Why performing?

J: Well, it’s the same thing. In this context. I mean the same thing.

B: OK. You said that’s what it was like on Friday and Saturday. What about last night? Perform?

J: It was like I… in those other ones, I couldn’t see the audience at first, so there was this moment of realization that people were watching me, and that was what brought me back to the real world. But this was like, right from the get-go, people were watching me, and I knew that so when I made eye contact with them, I tried to be as present as possible with them… I don’t know, I came back to the real world pretty quickly. I guess I was apologetic because the people’s faces… I dunno, that was my reaction. I think that that moment ended up being really profound, and I wish that I had something to say to be like, hey, this is why that happened. Because I think that it’s really interesting, and I think that looking back on it, I could come up with some rationalizations for what it is and what it’s about. The truth is, I had no idea what I was going to do when I got back downstairs.

B: You were up on the roof and you went until you couldn’t see a star anymore?

J: No, I didn’t do that.

B: You didn’t do that?

J: No.

B: So were you acting as though you had?

J: No. I was–

B: So, you said to me last night, you tried to picture the star in each person’s face.

J: Yeah. In their eyes.

B: But you hadn’t seen the star to begin with.

J: Right.

B: So it was the image of a star:

J: Yeah. Whatever their conception of the star was, that wasn’t a star, that was what I was trying to see.

B: So you were trying to see what they saw, and not what you saw.

J: Yeah.

B: And when you couldn’t see it, that was when you had failed?

J: It’s not like I set it up that way, but maybe. I mean, in the moment I just sat down and I looked. I didn’t know what I was doing. I looked into people’s eyes. I saw something that I didn’t want to see, or that I wanted to change. I was like, ‘sorry’, and I wanted to feel compassion and I didn’t and I felt like I was getting judged and I felt like it wasn’t right. Yeah. I don’t know, man. I don’t know why that performance. That’s the one I have the least explanation for. Whatever, I mean… maybe proof more than anything that anything can be a source of epiphany.

————————————————————————

A group of about a dozen people were there to see the performance. We were seated along one side of a long table on the first floor of 1419. One by one Jeff took us up to the roof and instructed us to lie down and focus on a star. Once we had forgotten that it was a star we should come back down to the first floor and sit on the other side of the table, at which point the performance would begin. It took about half an hour for everyone to go through this, at which point Jeff adjusted the chairs on the original (uniform) side of the table, facing the audience, and pulled one back. He sat in it, looked at each of us for a while, appeared apprehensive and nervous, and apologized several times, saying only “I’m sorry” or “I’m sorry, guys.” After maybe two or three minutes, he moved his chair back in line with the others, looked more settled or satisfied maybe, and then said, “OK, that’s it. Thanks for coming, guys.”

I was very moved. First of all, going up to the roof and focusing on a single star until I could believe that it was not a star… I felt very unsettled and a little twitchy coming down the flights of stairs back to the first floor. I had convinced myself that I was seeing a shuttle, or space ship. Somehow, that manufactured belief felt very destabilizing. Definitely a suspension. I couldn’t remember how many flights down I still had to go to get to the first floor (and I lived at 1419 for about half a year; I know those stairs up and down, through a whole spectrum of intoxication.) This simple exercise had recontextualized for me my surroundings, offering me a fresh and unfamiliar look at my world. I was in a heterotopia of one.

The sense of possibility awakened by this exercise was perhaps what Jeff referred to as the audience’s epiphany. It’s a really lovely idea of what the relationship between the ‘performer’ and the ‘audience’ can be—the performer facilitates the audience member’s imaginative epiphany—they are asked to suspend their disbelief, as I suppose audience members in most theaters around the world as asked to do. However, in this case the performance would not go ahead until that suspension had been accomplished. And the sole judge of that having been accomplished was the audience member her/himself. I thought it was considerate and respectful—asking the audience member to participate in the piece in this way, and allowing them to be the judge of when they were ready.

Knowing the performance was about to begin, and having prepared myself for it in this way, when Jeff reappeared after all the audience members had gone through their own suspensions, there was another suspension—that of waiting for the promised performance to begin. What I thought I was witnessing was the preparation for the performance—and Jeff’s inability to actually go through with it. And his unwillingness to abandon it. I was on the edge of my seat. Having gone through my own little process of committing to the piece, I wanted it to succeed, and I tried to send Jeff some encouragement. When he moved his chair back into line with the others and seemed finally settled and comfortable, there was a brief moment of triumph (it’s about to begin! Here we go!) and then, suddenly, it was over. It was a little bit of a roller coaster ride. I wouldn’t have thought so, and it may not seem so from the vantage point of reading this description, but having invested myself in the act of suspension, I was ready to be totally present with Jeff—and I was. To then find out that what I had witnessed was Jeff’s attempt to reconcile his own imaginative suspension (which was actually his imagining of what each audience member had created for themselves) with reality provided me a framework to organize my impressions. I could imagine that the piece was about the tension between epiphany and reality. Or the nature of epiphany—impossible to communicate.

The point isn’t that Jeff’s piece was actually about those things. The artist’s intentions ultimately count for nothing if the audience doesn’t get something out of the work. But Jeff had created the circumstances for me to experience something and then the conceptual framework that allowed me to organize that experience into thought. That’s what I like for art to do—to facilitate an experience and also provide a framework by which an audience can process that experience for themselves, and reach their own conclusions. Sometimes that framework is the artist’s bio. Sometimes it’s simply the title of a piece. Sometimes it’s a complex theoretical basis that produced the work. Access to this helpful framework varies—if a reference to something outside of the piece is necessary to contextualize the content of a piece and you don’t get the reference, well, you might not get the full content. I have a bit of an issue with work that depends on references that are overly esoteric or exclusive, by which I mean work that can only be fully understood by a tiny body of people. Art that only artists can understand runs the risk of solipsism. Sometimes art needs a bit of explanation, though, and I don’t begrudge that. I think it may be easier to work within those parameters in visual art rather than performance—an average ‘audience member’ is more likely to read a placard at an exhibition than to stay after a performance for a talkback. Could the helpful framework have been incorporated more fully into Jeff’s presentation? Maybe. The atmosphere after the performance was certainly conducive to a discussion of the piece, so it wasn’t such a big deal in the end. And had I known what was actually going through Jeff’s head during the ‘performance’ part, I probably wouldn’t have experienced such a provocative suspension; I might have known too much.

Below are further excerpts from my conversation with Jeff:

History of the Epilogue project:

B: When did the actual Epilogue project start for you?

J: It was 2007, it was freshman year and it kind of came from a couple different places at once. I was breaking up with my girlfriend, so that was… there was this thing that happened to me freshman year was I was sort of straight edge, not straight edge, but prude or, on the other side of the table from where I am now, if you know what I mean, and you do. And my girlfriend was very much on that same wavelength and when I broke up with her it was like a big push away from like all these accepted norms. … I was basically challenging what was going on around me, how things worked. That was the part of my brain that was firing then, I was like defiant and searching, definitely. At the same time, I was listening to a lot of Pinback… these things about post-apocalyptic or whatever… And at the same time, this phrase came into my head… I was thinking about love, and thinking about theatre… the thought of there being a finite amount of people on the planet, of there just being like 10, I thought of a true love that isn’t within the ten people. The little bit of dialogue that I of was like “She’s out there somewhere… How? Everyone else is dead.” Which is not that incredibly interesting, but I think it is… Anyway, that was like the seed nugget for, ‘OK, I’m gonna write a play about this!”

I had a class, and at the end of it we had to do something, so I wrote like four or five pages of the Epilogue Play. I was talking with Billy Mullaney a lot then, because he was right next to me in the dorms, we wanted to work together… I wanted to work on this.

B: What were those pages of Epilogue like?

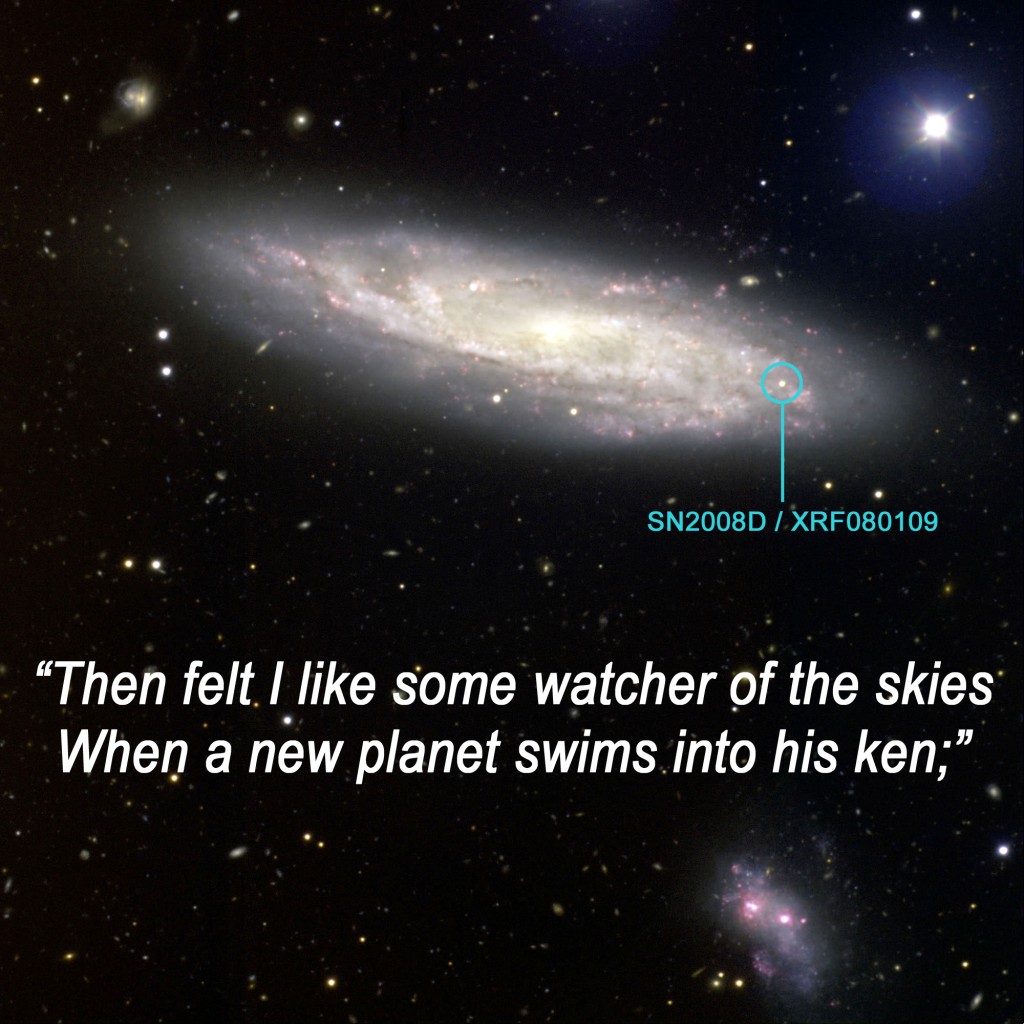

J: They were… it was like a normal play. There was dialogue, and these scenes… people came in and out of the scene. The only real developments–I think I had a scene about racing, how they couldn’t race anymore because there was nowhere to race to, and what was the point anyway. And I made a part about how this kid is trying to make a radio, and how they all think he’s really dumb for making the radio ’cause there’s nobody out there, but he wants his true love to be out there and find him on the radio. So that was basically it. Not even that many characters. That script I have not seen in years… There’s a strange love component to this whole project, in a way. It’s a part of me, and therefore a part of every relationship I’ve been in since I came up with it, or something. It’s like this thing that Jeff can’t, that Jeff is obsessed with… So that was freshman year. And then I became a stoner, I was smoking lots of weed with Maggie and Nick, Maggie Williams and Nick Marcouiller, they were good friends, and we decided we wanted to be collaborators, because we were good friends, and people called us the three-headed monster at that point. I talked with Nick this one night and we had this amazing conversation about how, like, everything was bullshit and people needed to get on a new track, you know, just, in the most general way almost. We had this whole thing about humanity; a lot of what we were thinking about was the difference between humanity and anything else. And especially thinking about outer space things, like other galaxies and stuff like that, how we understand those things in relation to us… It became this thing called Prologue/Epilogue, where Prologue meant everything before humanity and Epilogue meant everything after humanity, so it was kind of like this exploration in both directions of what human beings could never experience, or understand.

But it was trying to be really scientific about it in a way, we were trying to do like, ‘represent quantum physics with your body,’ you know, ‘do a supernova, physically.’ We were really struggling to get these huge concepts in our like, BA Theatre bodies, we were like… ‘Ooh, what’s this? Is this an explosion?’ It was ultimately unsatisfying for us, because we had so many thoughts about it, and so little ways to put it into practice. We only did one workshop for it.

B: I remember that.

J: We had a blog. We still have a blog, I guess. There’s a bunch of posts on there about what the Epilogue project is, links from Nick. Since Nick joined the project, that’s been a big part of the project, is Nick-links. Cause Nick knows a lot of things about links. Um… (laughs) So where am I at?

B: Junior year.

J: So junior year. When did I re-pick it up? I decided that I wanted to pick it up again in the fall, and I decided that I was gonna do it in the spring, 2010. I think at that point I wanted to do it into a play, that summer. Summer 2010. I submitted it for Fringe, I didn’t get in. That was the plan. I had six workshops in March 2010 with Celeste, because I had been talking with Celeste a lot about the Epilogue and what it meant. So again, it was another one of these, we’ve got a lot of theory going on, and we tried to put it into practice, and we were taking a little more organized approach than I had before, like, with the Viewpoints, we were doing straight-up Viewpoints exercises and modifying them. Doing a lot of sort of experiments where I had some parameters. The difference between that and this year’s project was that this year’s project I never knew what was gonna happen at any moment. I tried to plan it back then, you know, it was like, I have no books of ‘here’s what’s today’, and stuff like that.

It was clear to me a little while after that, thinking back, that I wasn’t gonna be able to make a ‘play-play’ out of this, the way that these ideas were going, I wasn’t making a play anymore. I had started that way freshman year, and then kind of got it confused sophomore year. So I was like OK… but I really liked the experiments where, I did this kind of ‘do what you feel, not what you think’ thing where… it was basically what I was trying to do in the first couple performances of this exhibition. Like, exist without thinking, exist within, not necessarily instinct, but in your non-rational place of being. And [in these exercises] there was like food, and chalkboard, and some random shit around, and people could mill around it.

I thought that they were really boring to watch, they were super boring to watch. But when I talked to people afterwards, they were like ‘Wow, that was really interesting to go into that mindset, that was really cool.’ So I began… I was thinking that the experiential was something that I wanted to get at, that these people in the workshops were sort of my audience, and I began to frame it that way. That like, especially since I had been talking about this for like three years at this point, and it basically had been nothing, the fact that so many people were checking in with me about the Epilogue project… meant that it was something already. So then I was satisfied with saying ‘OK, I’m gonna move on with this’ but in a way that wasn’t product-based really, as much as like, keep spreading the word, keep the momentum going–

B: Right, an experience–

J: And not placing particular importance on any one event. It’s just kind of, the idea, you know. And I applied for the X, for the 2010-2011 season.

B: The fabled season. [all four pieces of what eventually became the 1419 Theatre Season—WATERBOX, Romanian Revolution Project, erased bobrauschenbergamerica, and The Epilogue Project—all applied to the University’s student-run Xperimental Theater for their 2010-2011 season; none were accepted.—Ben]

J: Which none of us made it into. You know, for the exhibition on Sunday, I had out the last page from my X proposal. Which I liked. It was like, ‘I have a dedication to relevant theatrical experimentation, blah blah blah,’ it was like… I put it in line with the other bullshit. But anyway.

And then 1419 happened… was happening. I had been planning on doing it at 1419. And then the theatre season happened, Performance Playground happened… I think Romanian Revolution influenced me a lot, in terms of how I went about this, cause I had a lot of fun being, like, easy-going throughout the process on that, where I was invested in it in a way that was like… I didn’t feel like I was so a big part of it. It was something without me, and it was something with me, and I was really happy being able to come and go, and be there when I wanted to be. So I wanted to give people a lot of freedom, especially in a project that’s about human potential, I wanted to let people do what they would, basically. And I didn’t know how to do that… And I was up until January, up until then I was gonna still be making a performance, like, play. I had this concept of a machine and a crew, a machine of puppeteers that were like the spaceship that they lived in, and the crew was the people living there, so they’d be going through two different rehearsal processes, and I had it all mapped out… but then I was like, nah. Cause it would be great if people could just come whenever they want, and not feel like they were missing anything… Cause there isn’t anything to miss.

So I just started a facebook group, without really knowing what I was doing. And posted this thing about how this is my vague project, and here I am, Jeff Shockley, whatever. And then it just rolled. I didn’t think that that was gonna take off. Nick just posted a lot of stuff right away, which was great. And then, there was a lot of activity on there right away, and it just kind of fed itself. And I was like, OK, here’s the first meeting, and people were like, alright, and they came. And I was like, here’s the second meeting. I never made any effort besides facebook to advertise this year. And I didn’t tell people about it word of mouth, even, like specifically. Yeah. For some reason, I feel like that’s right. It’s kind of bad for people who don’t have good access to the internet… but it’s there, all the time, it’s permanent. It’s very cool, I like facebook. And then the retreat happened. And you know about that. For me that was… I didn’t think it would be that big of a thing for people… I thought it was going to be harder, and that we would be tired, and really happy to go home, you know. But, it didn’t. It was like, cult happy land, and we all wanted to go back immediately. We’ve been affected in different ways by it. I think that was when I decided, because that is the outcome that I want out of this project. Everybody having their own revelations. Having a big impact in their lives. And owning something that’s theirs. And I didn’t give them that revelation. They experienced it in a space that I created the potential for. And that’s important to me. Because I’m so against–I can’t deal with other people’s ideas all the time. That was a big thing for me, letting people, not making people. So in that sense it was like the biggest success I could ever think of. All these people being super proactive, and being there, and present, and helping each other. It was like, Wow, we really got there, wow. But there’s no one way to do that. And there’s no way to make sure that that’s gonna happen, is what I’ve kind of realized.

Intent/Expectations (and the difference between lifestyle & art)

Jeff: [about the Epilogue Retreat:]

When I look back at why that thing was magical, it just unfolded, it just kinda happened, the whole time. It wasn’t any decision that I made, certainly… I’m satisfied with that, and after that, I was like, OK, that kind of thing… for a long time I wanted the exhibition or the performance to be like that.

Where everybody is transported to this world together, the performers and the audience. Where they have this thing happen to them and they come back and have to reconcile. But I realized that that’s the setting where it happens more than… it could happen anywhere, but in a theater it’s gonna be hard to manufacture that experience… people aren’t gonna be willing to just go along on this journey… and then this talk with Broc I had after this last meeting led me to think that I should just do a strong gesture of what I thought I meant by all of this, sort of. Like, what am I doing? And just do it. So that’s why I ended up, just living on stage, and living outside, as sort of these things. I kind of instinctually created all the performances. Since I wanted to create them non-rationally, I didn’t pre-plan them. I would go to the space, I would be in it for a little bit, and then… sort of sense what I could do that was the Epilogue project there. I didn’t think I was gonna do a museum style exhibition on Sunday, but I did. I set up six objects and had people walk around and look at them. That felt like, OK, that’s what I can do here. That’s the potential here that I’m gonna use. And then last night I thought I was gonna do a performance on the roof, just me, and everybody watching, but then I was like, no, I think I want something else here. There are these chairs, and there’s these tables, and I let that all inspire me, and I was like OK, the stars are out, these things are gonna happen, that was all made in half an hour.

At this point, I think the Epilogue project is something that… it started out really small, then snowballed into, like, the biggest project that you could have, where it’s about everything and everything is in it, nothing’s outside of it, you can’t even directly address it because it’s so huge, but that’s also the beauty of it in a way, you know what I mean?

And that’s the purity that I want to keep in it, when I think of it. But I’ve gone as far as I can in that direction, I think. And now I want to be articulate, and say, we’re not all the way over there, we’re putting these limitations on ourselves, we’re making a play right now, we’re going to do it in a theater. But. There’s still the possibility for people to have these sort of revelatory moments–maybe even more so, than if it was somewhere else where they wouldn’t be predicting things, the way that you could predict them–the audience wouldn’t be expecting things that you would be expecting them…

B: What is the significance of those expectations? How do you put that to use?

J: People are sitting in a theater, looking at a proscenium stage. In my deconstructing everything mind, I would be like, Oh, that’s bad, that’s how it was, other people have made us do this, this is the tradition, I want to innovate. But then it’s like… yeah, but no. Everyone can sit down in the audience and look straight at a stage and still something new can happen. And, if people seek this kind of experience out of theatre, then why not use their journey of going to a theater to just do it? Isn’t that a ritual already, isn’t that a ceremony that gets people to the right state of mind to be viewing something? There’s a lot of these things where I’m like, well, we could be getting everybody to go into a field and stand in a circle and hold hands, but, we have these traditions already that we can use to a certain extent. Maybe there’s some that I don’t agree with, that need to be changed. But I’m sort of done railing against everything. A lot of this project was trying to do things that had never been done in ways that had never been done before. And it just keeps folding in on itself. It’s like… what’s recycled and what’s not? When you get down to it, it’s all recycled. How am I not just a product of everything that’s come before me, even if I completely innovate?

It’s been a good platform for me to think through things like that. Like, what does experimentation mean? What does collaboration, these big words of the program… and what does an art product mean, versus a life-style, what is art versus life-style. And I think that you don’t have to make the difference. I think we’ve gotten to the point where we can say that art is lifestyle and lifestyle is art, and you can prove that, go ahead. But it’s also kind of useful to make the distinction. I think.

B: Why’s that?

J: Why’s that?

B: Well, how is it useful?

J: Because when art is art it’s made to be art. Not that you can’t see art in things. But if I say, I’m an artist, and then I encourage people to eat more vegetables, and I consider that my art… Well, in a way there is art in getting people to improve their nutrition. A sort of underlying art to that, that’s beautiful in a way or something. But I think that kind of thought is done being useful to people. Everybody’s kind of heard that whole deal. Oh, art is everywhere, art’s all around us, beauty’s in life–OK. And people do see it, people find beauty in their lives all the time. Art doesn’t need to get people to do that. I think art can just be… in the most conservative sense, it could just be objects in a museum that people look at, and that’s a heightened setting, and that’s part of their lifestyle is interacting with that art, but a lot of what I was trying to do was to change the entire way that people frame their existence, and that’s, I just don’t think that’s possible, through an art kind of process. Through a hey, I made this, come look at this, I just don’t think it’s possible.

B: Is it possible through a life-style process?

J: I think so. That’s why I think a cult–that’s what you’re doing. You’re sort of aligning your life-styles. In a way that’s what we were doing at the retreat, we were aligning our life-styles. And in a way, art was part of that. We found art in things. But I think that overall that sense that we got was because our way of doing things was aligned.

B: Is it useful to make the differentiation because art’s scope is limited?

J: No… I mean, no, that’s not what I’m saying. I’m saying it’s useful to make the distinction so that artists stop trying to mess with people’s life-styles and try to call it art. I think there is an impetus within me to encourage people to have a certain kind of life. There’s plenty of plays that teach a lesson against hate or something. And that’s in a way a life-style suggestion, but there’s not, instead of making that play, where you show that in that art way, this would be like, the equivalent would be getting people into a therapy room, and saying like, OK, let’s talk about hate issues. And you can do that, and that does work to eradicate the problem of hate in families, but I think there’s something else that art offers. That’s this… like third party to life. It’s not as up in your business. You kind of get to make it up.

B: In creating it or experiencing it?

J: In experiencing it.

The role of science-fiction and utopias

B: How would you describe the connection between the presentations of this past weekend and science fiction?

J: The presentations of this past weekend and science fiction… um…

B: Because my read on it, I haven’t been all that involved in the facebook group, but my read on it is that a lot of the discussion centers around the idea of the future and science fiction and space.

J: Yeah. Yeah. That has a lot to do with it for sure. There’s a couple big ideas from science that are big in this Epilogue thought process. The thought of dark matter, that there’s a 90% of the universe that exists all around us and within us that is unknowable to modern science and we can’t figure it out. And… well, OK, science fiction, it’s the idea that the world that’s sort of outside of our current human experience, but isn’t made by magic or anything, it’s humans that have done this… it’s in a way really realistic or something…

B: It’s imaginable.

J: Yeah, it’s imaginable. It’s like… real humans in a fiction… confusing the real and the non-real is definitely why it’s interesting too. And imagining something outside of now. That’s the big thing. Science fiction is always written in the present, so as the person is writing the science fiction and thinking about the future or whatever they’re thinking about, they’re using what they know, what they’ve gained from everything that’s in their life to imagine something completely beyond it. And that’s totally, that’s a lot of what this is about, is conceiving that other space. And then… that exercise of, what is the utopia vision thing, what is it that I’m personally striving towards, what is it that I’d like to see the world be… I think science fiction affords people a way to write these scenarios out. Does that make sense?

B: Yeah.

J: As far as this weekend, the first couple [performances], I wasn’t really thinking about science fiction, I was more thinking on the planet, really. The Sunday and yesterday [Monday] were a little more space-oriented.

B: It’s interesting, because when I was looking at the star, it happened fairly quickly for me, I laid down and I said, it’s not a star, it’s moving toward me, it’s a spaceship. It’s not a star, it’s a spaceship. OK. And I got up to get down. And I had a half-whisper in the back of my head that was like, wait, are you being too facile, was that too easy, were you just like… were you not supposed to know what it was, just not know and sit in the not-knowing… But it was really unsettling, even having this idea that there’s this spaceship. Maybe part of it was the idea that there was something on its way. It was moving. I don’t know whether I thought spaceship because I had some preconception about the Epilogue, at least not consciously.

J: Yeah. I mean, that play I started freshman year is like a science fiction play. I don’t know if you know that I’m planning on continuing that–

B: No. You mean you’re not done with the project thing?

J: Yeah. I’m done with, for now anyway, I’m taking this step in doing a play. Gonna do a play. It’s probably gonna be on a proscenium. Set in space. Or underwater. I’m not sure. Underwater, I think. But yeah.

Heterotopia

B: It seems to me that science fiction is one of the ways that we have access to an idea of the heterotopia. To this space where everything is different.

J: But it puts it in this realm where it’s like, this could happen.

B: Right. And I think the retreat was all about heterotopia. And actually I thought that this exercise of, it’s a very simple task, right, you go to the roof, you look at a star, and when you forget that it’s a star, come back down. Right? What were the instructions specifically?

J: No, that was it.

B: And then sit in this other space. That to me seemed, it was a very simple and effective way to ask everyone to move into a heterotopia. Because the rules, the reality, were changed. And you had to change them imaginatively. And you were beholden only to yourself. You could say OK, now I leave the roof.

J: Yeah.

B: And so it was very individual. But at the same time it was communal. Because we were all basically engaged in the same activity. And then changed spaces gradually but together. And because this thing had shifted, it was sort of an open-ended question to me–what else could have shifted? And so when you came down and sat in front of us, it was, for me, this very suspended, tension-filled thing. Because I wasn’t sure what the rules were, because reality was suspended.

J: Cool.

B: I had a question about the experience of the private and the community, the social thing.

J: Yeah.

B: You were talking about last night, after the performance, the idea of wanting to create revelations, these epiphanies, and it seemed like the epiphany is a private journey.

J: Totally, it’s absolutely private. In a way that’s indescribable to anyone else. That’s how I think of it. Something that you can’t communicate, is something that’s epiphany.

B: And you said something about it being a journey of spirituality more than, maybe, art practice. That really made sense to me because I’ve thought for a while that the thing about religion or spirituality is that any kind of experience, any kind of authentic experience with the spiritual is inherently a private one. And that you can talk about it but you can’t actually communicate that experience to another person, it has to be an individual experience.

J: Totally. Yeah. The transition I’m making now is instead of cultivating this atmosphere of epiphanies, sort of trying to present a product of the impact of such epiphanies, and a story that people can get into of what it means to have an epiphany and come back. And just the whole notion of all of that. And in a way that people can understand. And when they understand that they will be able to use that as a lens into their life, to look at things differently.

B: Other people’s epiphany.

J: Other people’s epiphany–wait, what?

B: The story of someone else’s epiphany. You’re telling the story of an epiphany. So the audience doesn’t experience the epiphany, they see the experience of the epiphany. But they use that experience as a lens into their own life?

J: Yeah.

B: So, that seems to me a little bit different than the presentation last night.

J: Yes.

B: OK. So…

J: Like, I’m not gonna hold anybody’s hands anymore, I’m not gonna…

B: Uhhuh–

J: At least for a while, I’m not gonna talk to the audience directly, I’m not gonna be myself onstage. I want to present an art object to be viewed and interpreted.

Relationship to/influence of Relational Aesthetics

B: I think that it was out of your mouth that I first heard the term Relational Aesthetics. I had never heard of it. And then a few weeks ago I watched this super shitty documentary about Relational Aesthetics. Anyway, I inadvertently learned a little bit anyway. What I gleaned was that a lot of the artists who made work that could be called Relational Aesthetic are concerned with the social space, and with activating space for social purposes. And I know that you’ve been influenced by this movement, and that you find it interesting. Do you have anything to say about that?

J: Yeah.

B: About social space versus a private epiphany?

J: Totally. I think that–I like Relational Aethetics, and that might… I’m influenced by it. RA is not trying to aggressively get people to think anything, or change their brain waves in any way. It’s very much not even concerned about what they’re thinking so much as a space where social interaction occurs on an artistic level. So… they’re not looking at this thing in your brain as their art, they’re looking at the relationships you form with the other people in the room as their art. So like, Rirkrit Tiravanija’s noodle soup piece, where’s he’s serving noodle soup, and everyone’s there with the noodle soup together, and they’re eating their noodle soup, and they feel like they’re special that they’re there in the gallery and there’s this thing, and it’s different, and they kind of have this experience. And the art of that is this network of relationships that surrounds the piece. But it’s not the net change of thought–

B: Individually.

J: Yeah. And I think that’s the distinction that I didn’t make early on enough, is that I think that if RA takes as its theoretical horizon the entire social space, then my project was gonna take as its theoretical horizon the entire mental space.

B: The internal space?

J: Yeah, the internal space.

B: That’s interesting. I had always gotten the sense from you that the Epilogue was in fact about human relationships and not the individual. And how relationships would exist, could exist, without the context of culture, effectively. Of history, but, of context generally I guess.

J: Totally. But I think that the way that I’m trying to approach putting that into people’s heads is like, is not trying to create that relationship for people with another audience member, it was never, it was kind of…

B: I guess I would say that, the retreat, for instance, seemed to me to be about creating a heterotopic community, where we were able to see what our relationships to each other were, in a context-less context, where the context is written from scratch. Whereas the piece last night was about a heterotopia of one. Like the heterotopia was created imaginatively in our own heads, in our own universe, rather than, this room is a spaceship, the whole space being imbued with this from-scratch heterotopia.

J: Just something to maybe speak to that: a thought I’ve been having a lot recently is that we only know our own realities, and those epiphanies that we had on the trip, every epiphany you ever have… the social structure that we had there… what am I saying?

Well. You know. I’ve never known exactly what this is all about.

B: Yeah. Well, I’m not asking you to pin it down. Or maybe, I mean, I’m not asking you to pin down or specify the whole project. Obviously, I think that its nature is about being impossible to compass.

J: Yeah.

B: There’s maybe these specific points along this continuum of the Epilogue, different manifestations.

J: Yeah. That all have to do with each other in some way. It’s all about the human struggling to contextualize himself in a world that doesn’t seem right. Trying to imagine something else, trying to exist. For me it’s a personal thing. My existence in the world every day is troubled by thoughts of systems and how I don’t fit within them. It’s therapeutic for me in a way to give myself room to run with the idea of, yeah, heterotopic space.

B: Possibility.

J: Potential. Yeah, that’s something I’ve always been told is that I have a lot of potential. My mom always told me, oh, you have so much potential. That’s always been a big thing in terms of like guilt-tripping me, it’s like, if I do something wrong. Oh, you have so much potential and you’re just squandering it. So it’s been a big thing in my life. I think that might be a reason I’m obsessed with it. This idea that we can do a certain amount of things, or maybe we can do an infinite amount of things, and yet we do this. Yet we still do this. We could all just dismantle capitalism if we all just did it at the same time and we all just became farmers and just lived on the land again. I mean, it won’t happen, but it could. But it could, but it could.

B: Science fiction.

J: Science fiction.

B: That which we can rationalize as possible.

J: Yeah.

B: We don’t have to bend the laws of physics for this to happen. The ingredients are all here.

J: Yeah! There’s so many ways to contextualize who we are. And how we should live. That any two people will probably not agree. It’s very hard to work on that level of thinking. Like, how do I know how you think of yourself as a human? We’re not able to talk about that. I just am, and I always have been.